One Stitch at a Time: Fiber, Feeling, and the Radical Softness of Honey Pierre

This isn’t just fiber art. It’s a love language. Honey Pierre uses punch needle to stitch moments of joy, rest, and reclamation.

I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to be held by an image—especially in a world that so often demands we be strong, visible, and constantly producing. When I first encountered Honey Pierre’s work, I felt something shift. Her portraits don’t just depict Black and Brown people—they honor us, in moments of rest, reflection, softness. Through punch needle embroidery, she creates textured portals into emotional landscapes we don’t always get to linger in. The work is quiet. Tender. Unapologetically full of care.

Spending time with her words and her work reminded me that joy isn’t something we earn—it’s something we’re allowed to live in. I’m grateful to share her story with you.

Honey Pierre’s work doesn’t just invite you to look—it dares you to feel.

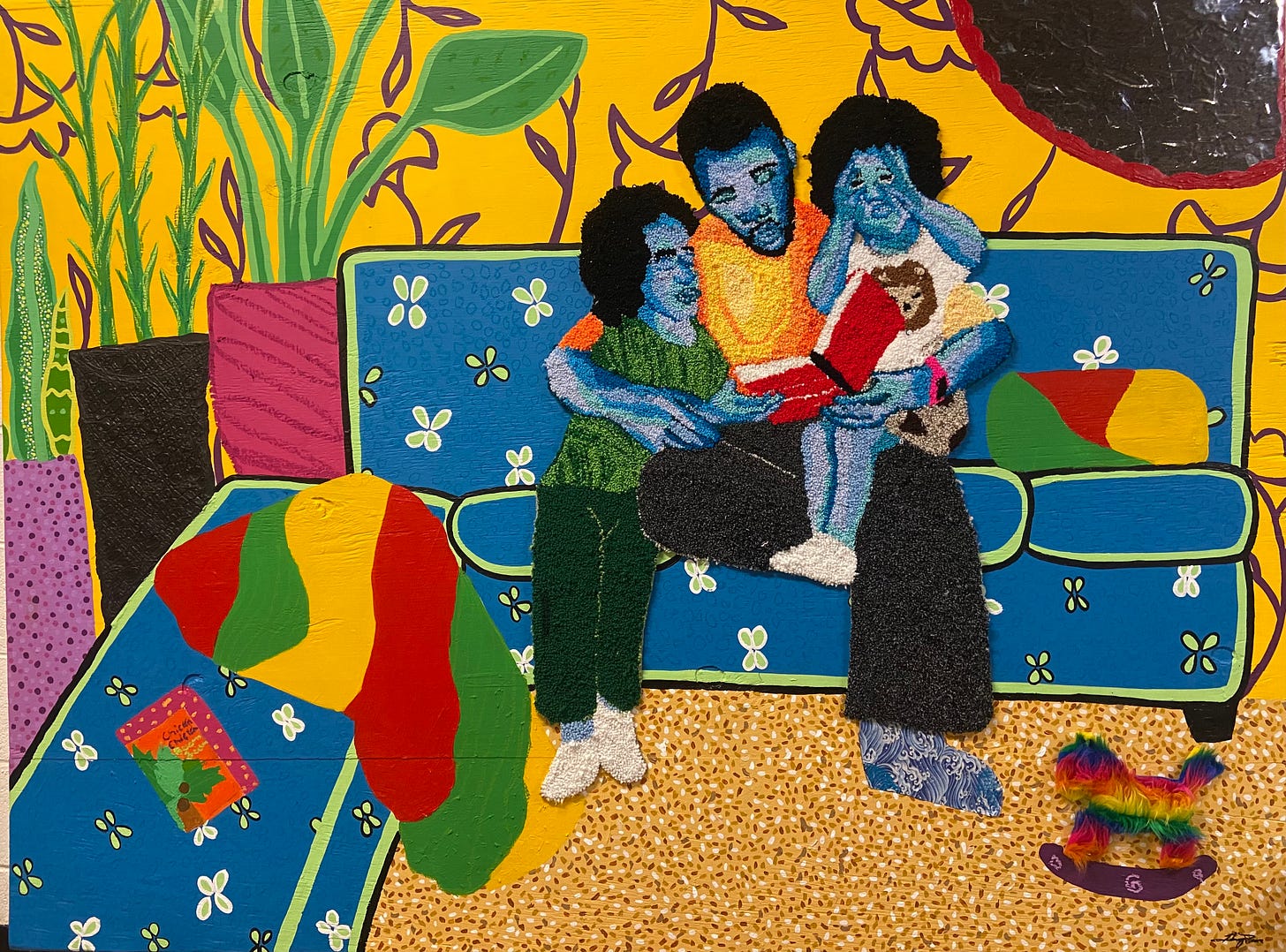

The Atlanta-based artist uses punch needle embroidery to create richly textured portraits that center Black and Brown people in moments of softness, introspection, and joy. With bold compositions, layered fabrics, and skin rendered in vivid shades of blue, Pierre weaves intimate, defiant stories that challenge what it means to be seen.

Pierre didn’t begin her journey in an art school studio. Born and raised in Cleveland, she found her creative footing only after leaving the military. Returning home, she became a tattoo apprentice and body piercer—a path that unexpectedly shaped the way she now approaches portraiture. Working directly with the human body taught her how to read form, motion, and anatomy, laying the foundation for her later work in fiber. That sense of physical connection remains at the heart of her practice today.

Her discovery of punch needle came during the pandemic, as she searched for a medium that wouldn’t aggravate her respiratory system the way oil paint fumes or charcoal dust could. Punch needle is a fiber art technique that uses a hollow needle tool to push loops of yarn through fabric, creating a raised, textured surface—almost like drawing with thread. A YouTube tutorial on rug-making set things in motion. The repetitive, tactile, controlled act of punch needling felt familiar, echoing the precision of piercing. Inspired by an interview with Bisa Butler, Pierre saw the possibility of bringing textile techniques into the realm of fine art. What began as a workaround became a signature.

There’s a methodical rhythm to Pierre’s process. She writes before she creates, drafting the emotional or narrative tone of each piece. She selects a model—often someone close to her—and stages a reference photo. Then comes the sketching, the threading, the painting. Her portraits emerge slowly, thread by thread, story by story.

One of the most striking elements of Pierre’s work is her use of blue to represent Black and Brown skin. What started as a practical frustration—struggling to find the right yarn shades—became a powerful visual choice.

“Blue became a way to represent our vastness, our beauty,” she explains. “It wasn’t about realism, it was emotional.”

The shift was also a response to the language of microaggressions. “People would call us all types of names: blue, too dark, too this, too that,” she says. “And it’s just like, no, we’re not. We’re beautiful. This is our skin. This is what we’re in.”

That reclamation shows up in the themes she explores. While her work doesn’t ignore struggle, it intentionally centers rest, tenderness, and everyday joy. In an art world saturated with depictions of Black trauma, Pierre offers a different lens.

“Joy is radical,” she says. “I want to show us resting, laughing, connecting. That’s the beauty of who we are too.”

Motifs like florals and vines appear frequently, grounding her subjects in a world that feels natural, cyclical, regenerative. These symbols are autobiographical, too. When Pierre’s mother bought her first house, she didn’t rush to paint the walls—she went straight to the soil and planted a garden.

“Nature is symbolic: the cycles of growth, death, rebirth,” Pierre says. “You can replant yourself and still thrive.”

Pierre’s practice is part of what she sees as a larger renaissance in fiber art.

“A lot of artists are returning to what feels familiar—what they saw growing up, or what they’re just now picking up and making their own,” she says. Having learned the craft later in life herself—“My mom doesn’t even know how to sew,” she laughs—Pierre sees this resurgence as both personal and political. Long dismissed as “women’s work” or craft, textile art is finally being recognized for its power, its history, and its innovation.

Atlanta has played a key role in that evolution. Its Black art scene, she says, is one of the most supportive in the country.

“Atlanta’s Black art community rides at dawn. We really show up for each other.”

That spirit of mutual support has fueled her creative momentum—and deepened her belief in art as a communal act.

At the core of Honey Pierre’s practice is care: for her subjects, for her community, and for the slow, deliberate act of creation. Through punch needle, she brings forth images that are as emotionally rich as they are visually textured—portraits not just of people, but of presence, persistence, and possibility.

If you’re in Atlanta, you can experience Honey’s work in person at her upcoming solo exhibition, I’m Just Living Some Life, Okay?, opening April 18 at Impossible Currency Gallery. The show explores emotional, mental, and spiritual wellness among millennials and Gen Z through textured portraiture and radical softness. An artist talk hosted by Kent Kelly will take place on April 27—don’t miss it.

Truly at a loss of words after reading.

The writing is so poetical, and I love the personal position you took, articulating the joy and tenderness that the work meant to you. Thank you for sharing.