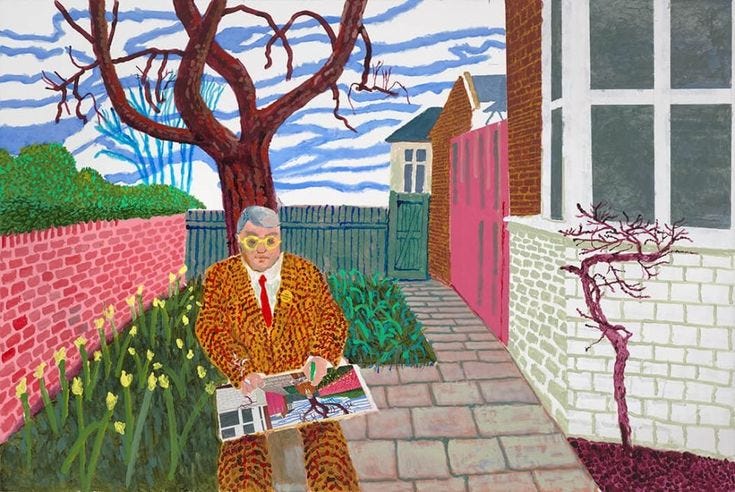

I’m heading to the Louis Vuitton Foundation this week to see David Hockney: Normandy Portraits, but before I even get through the doors, I’m already thinking about what’s missing: the exhibition poster. Or rather, the right exhibition poster—the one Paris banned. A simple Hockney self-portrait, drawn in his signature scribble: eyes peeking through oversized glasses, a cigarette tucked between his fingers, lines of smoke curling up like they’re flirting with the sky.

Apparently, that was too much for the French government. The image, they argued, promoted smoking. And so, in a city where café terraces are fogged with Gauloises, and smoking is still treated more like a vibe than a vice, they drew the line at a pastel puff of smoke.

It makes you wonder: in a place that has long aestheticized the cigarette—made it synonymous with allure, rebellion, even chicness—what happens when the image becomes unacceptable? What’s really being banned here—the cigarette, or the right to make an image that tells the truth about the culture holding it?

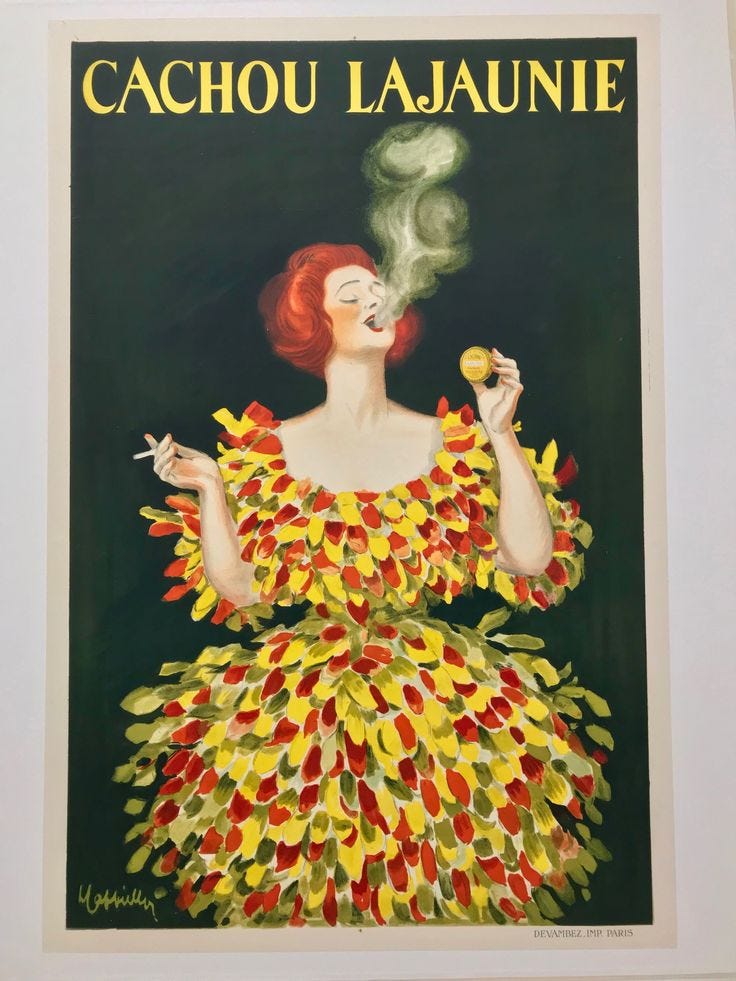

Long before the French government decided to protect the public from cartoon smoke, the image of a cigarette had already burned itself into the collective image of Parisian life.

Cigarettes appear in the art of this city not as props, but as symbols—of mood, rebellion, eroticism, thought. They curl through oil paintings, sulk in black-and-white photographs, and dangle from the fingers of muses, mistresses, and mythologized intellectuals. In the Paris of art history, smoke isn’t a vice—it’s an atmosphere.

Start with the cafés: Montmartre, Pigalle, Saint-Germain. Toulouse-Lautrec captured dancers and drinkers, their silhouettes smudged with absinthe and haze. Degas gave us ballerinas and brothels—his women often pausing between movements and meaning.

Even Picasso couldn’t resist the visual pull. In countless portraits, the cigarette is there, sometimes barely a detail, but always deliberate. A shorthand for something you can’t quite name—power? freedom? An indulgence dressed up as sophistication? A touch of decadence mistaken for depth? Or maybe that’s the same thing?

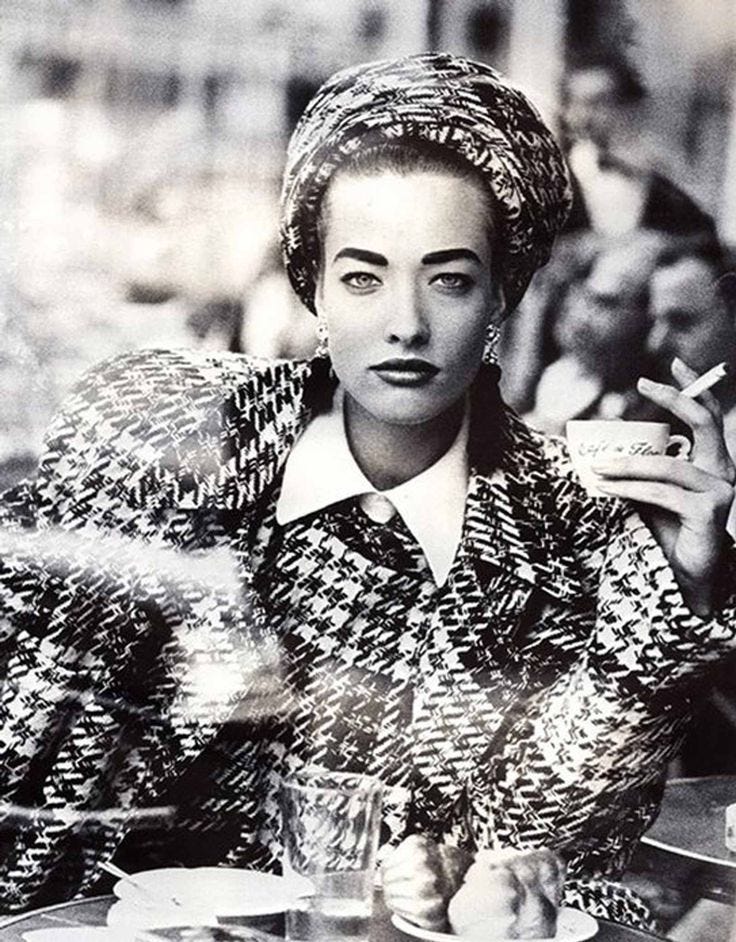

By the time the postwar existentialists moved in, the cigarette had gone from background detail to central motif. Sartre and de Beauvoir chain-smoked through philosophy at Café de Flore, building an entire identity around intellectual discontent—smoke was the punctuation between thoughts.

Photographers like Brassaï, Cartier-Bresson, and Ed van der Elsken documented Parisian nightlife not with flash, but with shadow and smoke. Their images made it clear: to be in Paris and not smoke was to somehow be out of step with the performance.

And then there’s the cigarette-as-accessory to feminine defiance. Man Ray’s portraits of Kiki de Montparnasse show her half-dressed, half-laughing, cigarette in hand—neither muse nor masterpiece, but something in between.

The smoky image of Marlene Dietrich, suited and smirking, became a visual middle finger to gender norms, especially once she lit up.

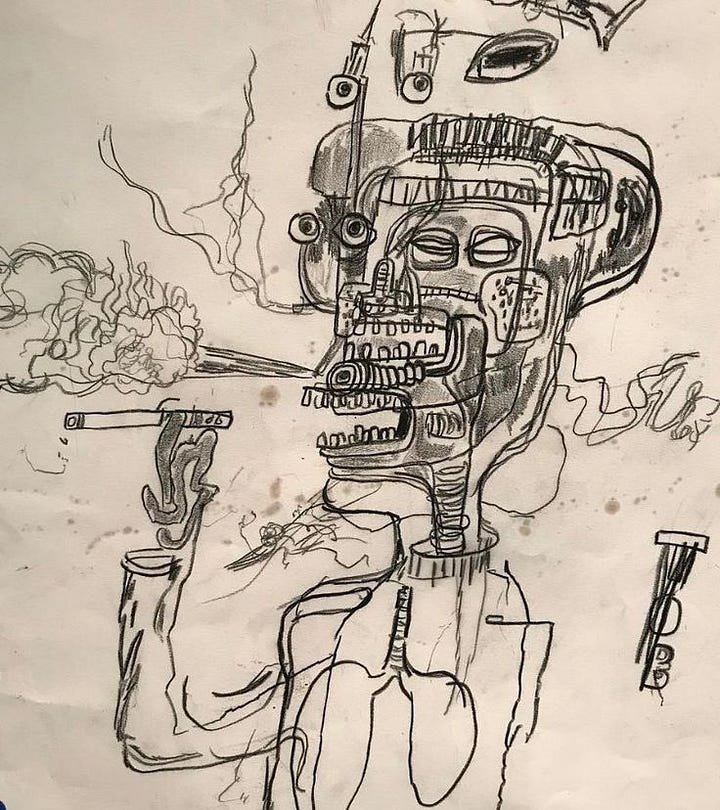

And the imagery didn’t stop with the existentialists. Artists like Andy Warhol, who split his time between New York and Paris, turned the cigarette into a pop object—flattened, fetishized, mass-produced. Jean-Michel Basquiat, often captured smoking in photos and depicted with cigarettes in his paintings, transformed it into a mark of defiance, decay, downtown cool. Even today, the cigarette still flickers at the edges of the frame—not because it’s fashionable, but because it’s a symbol that won’t burn out.

The cigarette in art was never about the act of smoking. It was about the attitude. Power, seduction, class, rebellion, melancholy—the very ingredients of the Paris we still try to imagine. To erase it now doesn’t feel like health policy. It feels like revision.

Which brings us back to Hockney. Because if the cigarette in art has always been about attitude, the banned exhibition poster was the attitude Paris suddenly couldn’t handle.

The drawing itself is classic Hockney—simple, vibrant, and unmistakably him. A self-portrait full of loose lines and controlled chaos: oversized glasses, a squiggle of smoke, and that familiar cigarette perched between his fingers like a comma in an unfinished sentence. It’s not glamorous. It’s not edgy. It’s barely even promotional. But it was too much.

Too much, apparently, for a city that built its aesthetic legacy on a cloud of smoke and a shrug of cool. A cigarette on a café terrace? Acceptable. A cigarette in a Hockney drawing? Dangerous. That’s not public health—that’s optics.

And that’s the irony. The image doesn’t glamorize smoking. If anything, it demystifies it. Hockney, now in his eighties, is no rebel enfant terrible. He’s a legacy artist—a man drawing himself with the same cigarette he’s always held, even as the world around him changes. There’s something almost tender about it. Honest. A record of habit and identity and time.

So what exactly is the threat? That someone might look at the poster and suddenly want to start smoking? Or that someone might look at the poster and remember that art is supposed to reflect us, not correct us?

France is entering what can only be described as its clean-up-the-act era. Starting July 1, smoking will be banned on beaches, in parks, and near schools—with fines to follow. It’s a public health move, and sure, it makes sense. But banning Hockney’s exhibition poster? That’s not about health. That’s about optics.

Meanwhile, inside the Centre Pompidou, Beauford Delaney’s Auto-Portrait, cigarette in mouth, hangs quietly in the Paris Noir exhibition.

Just across the Seine, the Musée d’Orsay is presenting Apéritif and Showmanship, an exhibition celebrating the glamour of Belle Époque soirées—complete with pastel portraits of elegant women smoking.

The Musée du Fumeur exists entirely to preserve and display smoking culture.

How do you ban an exhibition poster when the city literally has a museum dedicated to the very thing you're trying to hide?

You don’t get to censor a drawing while operating a museum that sells souvenir ashtrays.

The poster didn’t glamorize smoking. It revealed the absurdity of pretending one image could erase what’s embedded in the culture—what’s long been part of the myth, the allure, the identity of the city itself. To censor that—while museums still show it, while a museum literally preserves it—isn’t policy. It’s performance.

You can ban the poster, but the smoke still lingers.