Still Building: Frank Bowling’s Material Abstraction

A reflection on “Collage” at Hauser & Wirth Paris

Frank Bowling is 90 years old and still painting every day. His first solo exhibition in France—yes, first—opened this spring at Hauser & Wirth Paris, and it is a masterclass in texture, technique, and time. Titled Collage, the show gathers works from the early 2000s through today and makes a case that Bowling isn’t just part of the conversation around abstraction—he expands it.

This isn’t collage in the cut-and-paste sense. Bowling’s surfaces are built—stitched, poured, layered with found objects, and sealed through a technique called marouflage, the process of adhering painted canvas to another support, often using glue or paste. While it has roots in European mural painting, Bowling repurposes it with an improvisational touch, using it to layer, fold, and reconfigure fragments into something tactile and alive. The marouflaged surfaces crack and ripple, holding memory like skin.

His approach to collage expands beyond form—it’s a philosophy of construction. In Bowling’s hands, marouflage becomes a way of thinking about time, movement, and meaning. He uses it to complicate the surface, to make room for texture, rupture, and return. It’s not just about how the work looks—it’s about how it holds.

This layered sensibility reflects the broader range of influences he carries. Bowling draws from both the English landscape tradition and American abstraction, and the tension between the two gives his work a kind of visual pressure. Geographies collapse. Color takes on weight. Figuration slips in and out of focus. “I was always very conscious of scratching out and of new interpretations replacing the old,” he once said. “Updating traditions.” You see that here—but it’s more than an update. Bowling isn’t referencing tradition so much as absorbing it, metabolizing it, and then inventing a language that’s entirely his own. A language made of surface and rupture, sediment and light. His work doesn’t just respond to art history—it insists on a new vocabulary for seeing.

Orangecentered (2023)

The first work I was pulled toward was Orangecentered (2023)—a monumental composition measuring over four meters wide. A saturated burst of orange anchors the center, but it’s not just a color field. It’s alive. The orange glows and bleeds outward, framed by surfaces that are cracked, wrinkled, and thick with accumulated time. You don’t look at the painting—you move through it.

Embedded in the work are unexpected fragments: a paintbrush, strands of string, pieces that feel both random and inevitable. The string doesn’t neatly stitch anything together—it wavers, floats, hangs—but it gives the work a kind of internal logic, as if the painting is holding itself in place. Bowling uses collage not as juxtaposition, but as structure. Lines and shapes emerge not to resolve the composition but to give it dimension—visual scaffolding built from intuition. There are gestures that feel loose and offhand, paired with forms so precise they nearly hum. The choices feel lived, not theoretical. This isn’t a work you decipher—it’s one you feel.

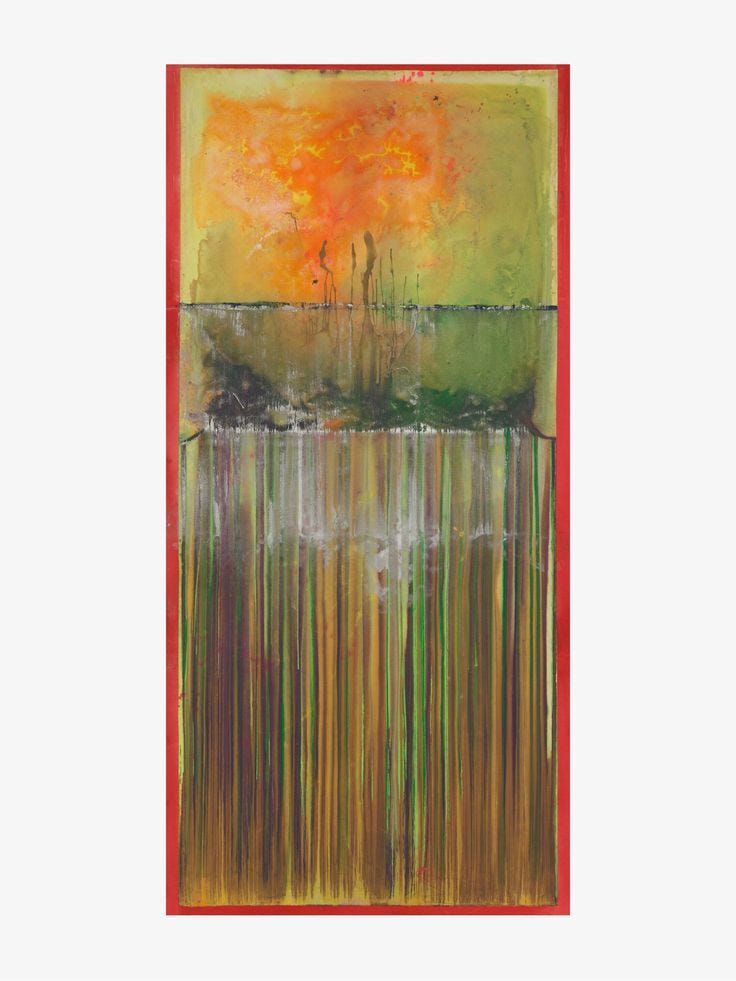

Dancing (2023)

There’s a kind of syncopation to Dancing—shapes that flicker, strokes that feel improvised but intentional. It doesn’t illustrate dance so much as embody its rhythm—repetition, sway, the echo of motion left behind.

The canvas is animated by contrast: at the top, bursts of yellow, orange, and green rise like light caught mid-motion—vibrant, flickering, almost weightless. At the bottom, elongated drips pull downward, anchoring the composition. At first glance, they may seem haphazard, but that’s where the precision lives. The painting doesn’t move in one direction—it moves in conversation with itself.

This is where Bowling’s control becomes most apparent—not in tightness, but in timing. The dance isn’t just in the brushwork; it’s in the tension between restraint and release. Between color that hovers and form that falls. Between what rises and what holds. Dancing doesn’t perform for the viewer—it moves on its own terms. And if you let it, it pulls you into that movement too.

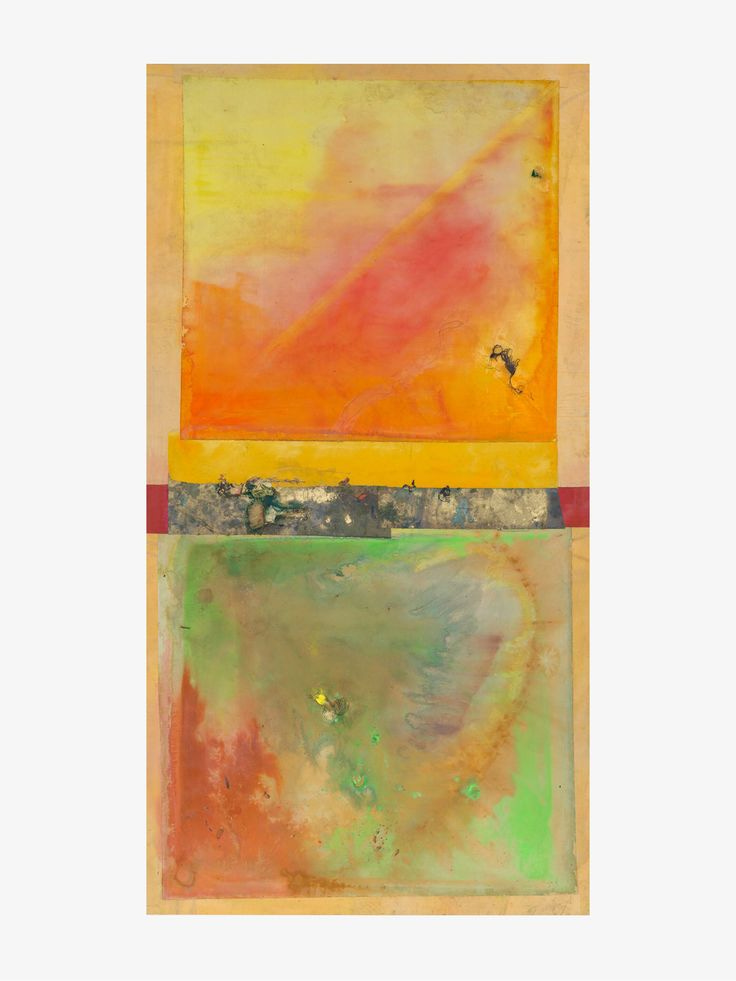

Dawn (2023)

If Dancing is all rhythm and movement, Dawn is breath. The painting opens slowly—light rising through layered translucence, soft tones of yellow, white, and green working their way upward like the first hints of morning. But there’s no sentimentality here. Dawn isn’t about a sunrise—it’s about emergence. About what it feels like to move from one state into another.

The composition holds its tension quietly. The surface appears almost weightless, but the gestures are deliberate. Color is thinned, spread, and softened, but not erased. You get the sense that each mark was pulled forward from something buried beneath. There’s care in the restraint—Bowling never overstates. He lets the painting breathe on its own.

There’s also a conversation happening between the layers. Like Dancing, Dawn plays with the relationship between what sits high on the canvas and what gathers at the bottom. One rises, one pools. In Dawn, the palette is gentler, but the intent is just as clear: something is coming forward. Quietly. Persistently. The stillness hums.

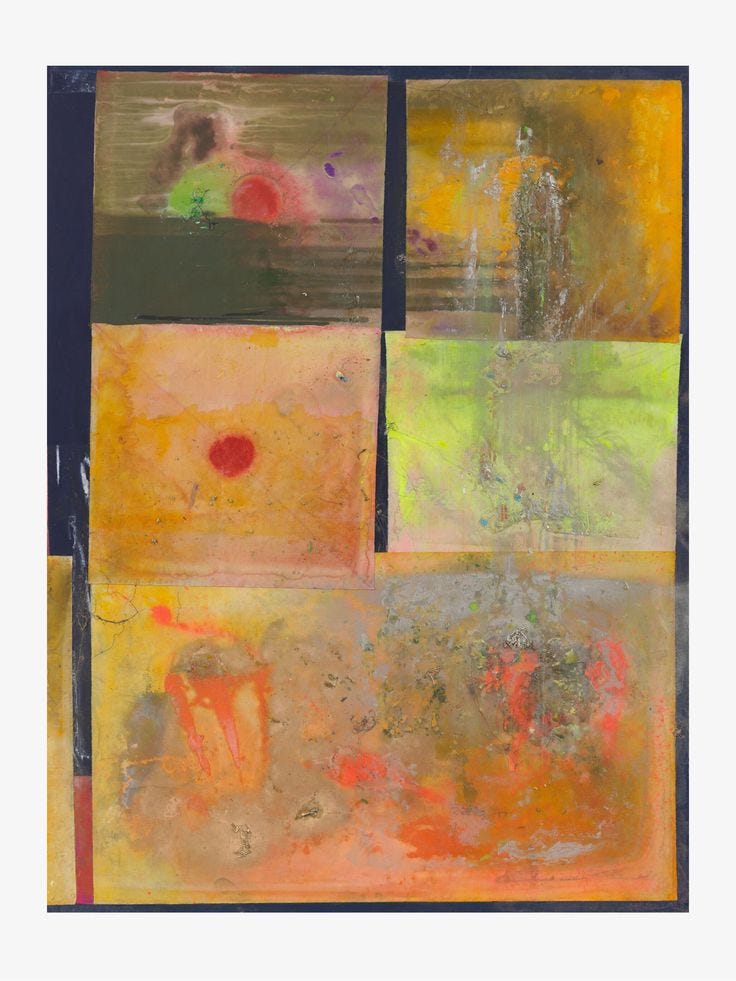

Skid (2023)

Skid is the largest and most physically dense work in the exhibition—over four meters tall and stitched from six separate panels. It looks, at first glance, the most like collage in the traditional sense: layers on layers, fragments clearly added and assembled. But standing in front of it, the longer you look, the less certain the structure becomes.

Objects are embedded into the canvas—some recognizable, others obscured. Is that medical tubing? A length of cable? Studio debris? You get the sense that each element has its own history, but Bowling isn’t offering a key. He’s asking you to sit with the ambiguity, to notice how the material holds memory without explanation.

The title—Skid—suggests something abrupt. A sudden stop. Or the trace left behind after movement, after contact. And that’s how the painting functions: not as a moment frozen in time, but as its aftermath. The gestures here are heavier, the layering more forceful. It’s a work that resists resolution. Every time you return to it, something shifts—a new texture, a new shape, a new question.

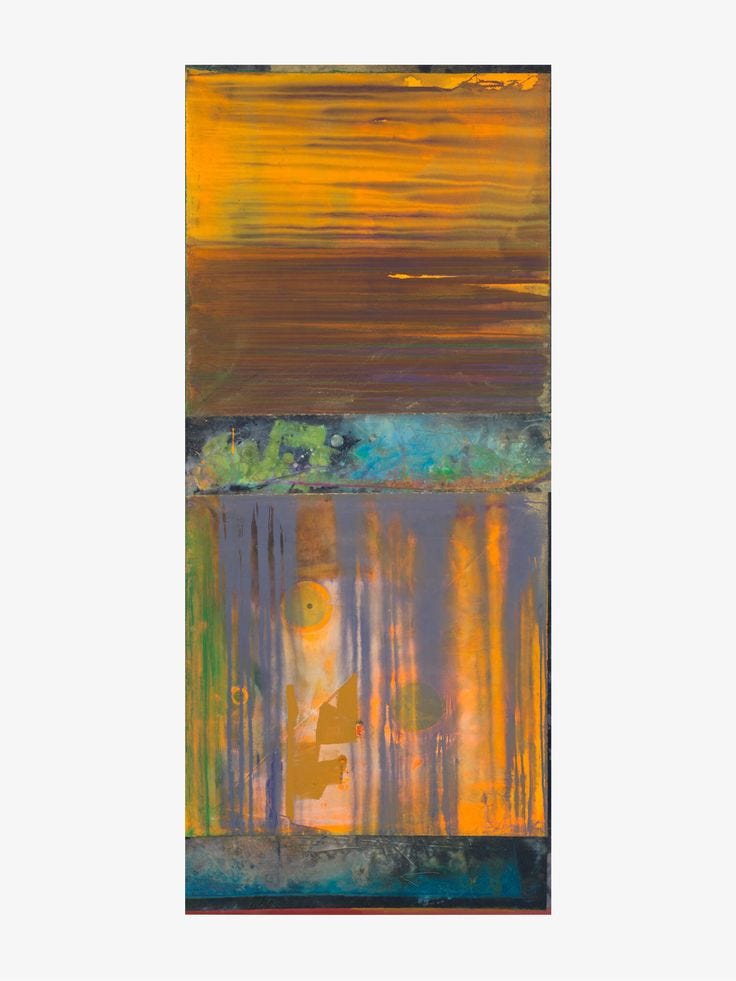

Water (2024)

Water doesn’t flow so much as hover. Bands of color drift across the surface—green shifting into blue, yellow bleeding softly at the edges. But it’s the flashes of red and gold that catch you off guard. They don’t dominate, but they gleam—like light breaking through cloud cover. The palette reminds me of the ocean at dusk, or the sky over the beach back home in Los Angeles. That moment just before the sun disappears, when everything is saturated and suspended.

The more I looked at the painting, the more the title started to shift for me. It’s not water in a literal sense—it’s the reflection of it. The color water takes on at sunset. The way it holds light and movement without ever fully giving itself away. The surface is layered, yes, but it’s also open. It lets you in slowly.

The colors don’t assert themselves all at once—they arrive in waves. One moment the painting feels cool and expansive, the next it glows with warmth. There’s something Rothko-like in that rhythm—the way color holds emotion, the way stillness becomes a kind of presence—but Bowling’s surface is more unsettled. More alive. This isn’t a painting that asks to be deciphered. It asks to be stayed with.

Pallings (2024)

Pallings is one of the more enigmatic works in the show. It doesn’t have the immediate clarity of Water or the structured pull of Skid. It holds its tension differently—through color, compression, and surface friction. The palette is sharper here: bolder contrasts and scraped, textured areas that feel almost bruised.

The title is curious. Pallings suggests intimacy—pals, closeness—but it also echoes pall, as in a veil, a heaviness, a shadow. That duality feels embedded in the composition. A dominant field of red is interrupted by a jagged yellow band at the top that bleeds downward. In the first third of the canvas, a vertical strip the color of parchment rises slightly off the surface, like a seam or scar. Embedded in that strip are found materials—a plastic shipping envelope, what appears to be a key ring, and other fragments I couldn’t quite identify.

Whether intentional or not, it made me think of the debris of departure—the ordinary stuff that lingers after a life has been packed up. Perhaps they’re the pallings of a move. A residue of transition. Not quite remnants. More like markers of presence.

What holds the painting together is its refusal to resolve. Where Water opens up space, Pallings presses in. You sense the labor in the surface—the physicality of application, the force behind the marks. It’s not a chaotic painting, but it’s not at ease either. It sits in that generative discomfort. Not everything needs to settle.

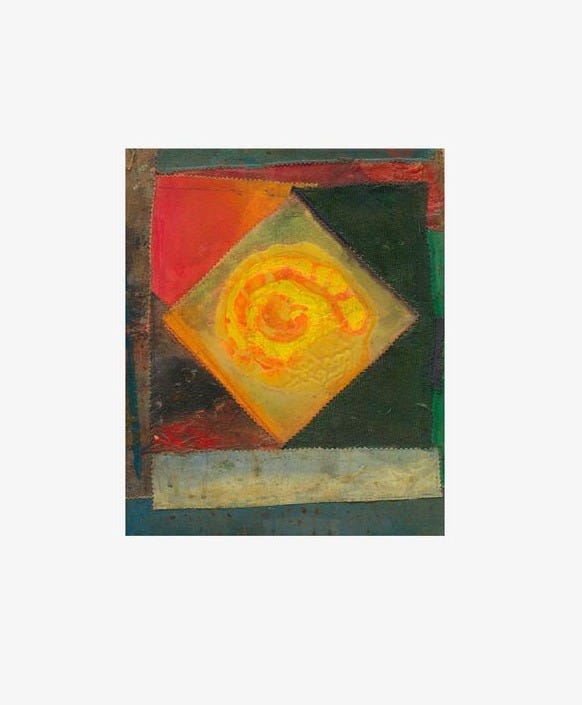

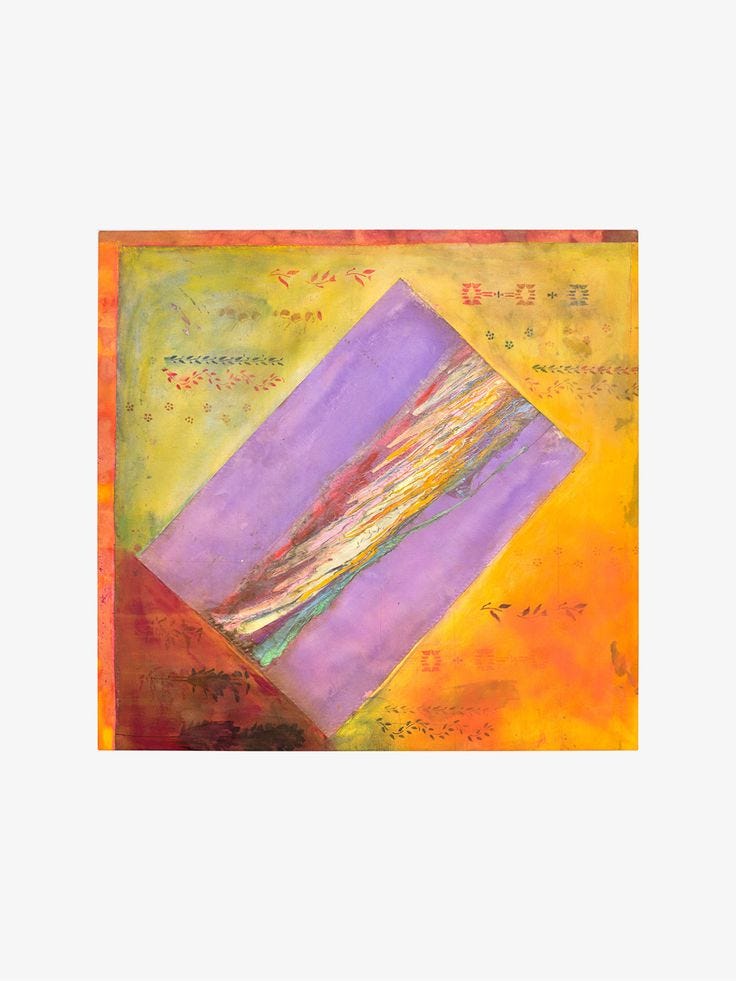

Wadi ✔ One (2011)

Wadi ✔ One doesn’t blend in—it reorients. The painting’s surface is alive with color: blues, reds, oranges, and yellow swirl and clash across the canvas. Floral motifs—almost stamp- or stencil-like—float across the background, adding a rhythmic, patterned layer that feels both ornamental and coded. At the center, a lavender-toned rectangular canvas sits diagonally, like a portal or a window interrupting the space. Within that, a spiral of layered paint blooms: dense, sculptural, deliberate.

This is where Bowling’s ambition for the series feels most fully realized. “I wanted to marry up all these disparate bits like color, mannerism, where you paint, this fandango of all these styles and make up a sort of strong work that has aspects of painting and sculpture and architecture,” he’s said. “They can hang together like something new.”

That’s exactly what Wadi ✔ One does. It doesn’t evoke memory like Water or Pallings. It asserts structure, presence, possibility. It feels plotted, but not static. The embedded canvas tilts the whole frame into motion, turning surface into object, image into intervention. If the other works lean into feeling, this one leans into construction. It’s not just built—it’s engineered.

Closing Reflections

Seeing this body of work in person felt urgent. Monumental, yes—but not in the way that demands spectacle. More like: this matters. This needs to be witnessed. There was no seating in the gallery, but I found myself wishing for a bench. Not because I was tired, but because the paintings asked for time. You needed to stand back to feel their scale, then lean in to trace the fragments and folds. The color. The textures. The layers. The choices. Each one deliberate, but none of them fussy.

It struck me that Bowling is still experimenting: still pushing, still layering, still inventing. There’s a vitality in this work that feels almost youthful, yet it’s grounded in the weight of a life deeply lived. That ability—to create with such freshness, clarity, and purpose after decades of practice—is rare. And it made me reflect on how abstraction by Black artists has so often been sidelined, misread, or reduced. Bowling isn’t just expanding the language of abstraction. He's developing a new dialect: one rooted in material play, personal memory, and a refusal to be contained.

He shows that material can be more than surface—it can be structure, site, and language all at once.

This show reminded me why I do the work I do. It reminded me of the privilege of seeing, of writing, of being present with the work—especially while Bowling is still here. And it reminded me of the responsibility: to not wait until the retrospective, the obit, the canonization. To give the flowers now. Because it’s not just about honoring the past—it’s about acknowledging the present. We have to make space for the greats while they’re still here, to ensure they are part of the conversation, not just subjects of posthumous praise. Seeing Bowling’s work up close, knowing he’s still building, still experimenting—it’s a reminder that legacy isn’t something we look back on. It’s something we participate in, now.

All images courtesy of Hauser & Wirth, Paris